words // Nick DePaula

interview & images // Zac Dubasik

As published in Issue 36 of Sole Collector Magazine

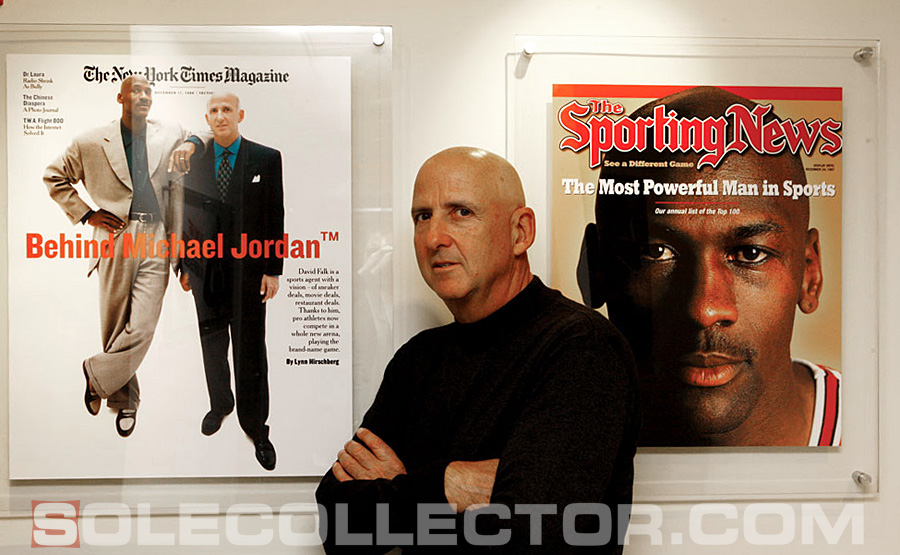

Click here to read Part 1 / 2 of Industry Insider. For more insights from David Falk, be sure to check out his recently published book, The Bald Truth.

As arguably the most notable agent in all of professional sports, David Falk has surely been there every step of the way during the NBA's considerable evolution over the past three decades. He's not only witnessed firsthand the similar rise of the footwear and sports marketing industries -- he's played an instrumental role in basketball's biggest landmark contract and endorsement deals. As yet another NBA lockout potentially looms this fall, Falk was even a major player during the league's Collective Bargaining Agreement negotiations of a decade ago.

With more than thirty-five years of experience, Falk currently prefers to think of himself as more mentor than agent. He enjoys being relied on for sound advice from the less than ten players and "great guys" he represents, certainly a departure from the days in which he represented as many as forty players. With the ever-changing world of corruption throughout both collegiate and AAU basketball something he simply won't deal with, Falk is at peace with missing out on many of the game's stars of today.

Enjoy the second half of Sole Collector's exclusive interview with David Falk below, as he discusses the changing footwear landscape, the lasting impact that some of his clients have and haven't made on their communities, the negative impact that AAU basketball has had on the game, and how he views himself now in the later stages of his career.

Zac Dubasik: With the new CBA coming up, and the cap looking like it’s going to be lower, do you think you will have more pressure from clients to make up for their lost contract money?

David Falk: I don’t think the cap is going to be lower. I think they’ll lower the percentage of revenues at the end of the day. But I don’t think they’ll ever lower the cap.

Whatever ends up changing, though, do you think that will impact the importance athletes are going to place on their endorsements?

Sure. I’ll put it this way; I think that right now, we are at a really difficult time with the economy. I don’t think the economy is going to change significantly for the next three to five years. I think we are going through a very difficult correction period, and we’re paying for many mistakes we’ve made over a long period of time. One of the biggest of which, in my opinion, is not allowing the natural business cycle to take effect. There’s nothing wrong with inflation. Inflation is a natural part of the business cycle; it’s a correction. . . . I think that we have suppressed inflation. I don’t know how we are going to wash the excess debt from our system without having inflation. As an econ major, I’m not smart enough to understand that, but I’d expect that we are going to have a lot of inflation sometime in the next two or three years to flush the excess cash out of the system.

So, the point I was going to make is that I think that with players today, everyone wants to be on TV, everyone wants to be on a commercial, they want to be on billboards, they want to be on the ’Net. There’s only a very small percentage of players – a handful of players, forget a percentage – in the whole League that are truly national. Most players in team sports are local. If you are on the Seattle Seahawks, you are not going to be that popular in Miami, FL. If you are on the Boston Red Sox, you probably aren’t going to be very popular in New York City. There are very few Peyton Mannings in football; there are very few Michael Jordans and LeBron James’ in basketball – there just aren’t. There are very few Derek Jeters that are national guys; most of their marketing is local. I think a lot of people, because there is a rookie wage scale (in the NBA), appeal to these young players that they can do all these great marketing things, but I think the market is pretty tight right now.

What do you think when you see a guy like Antoine Walker, for example, struggle after retirement? You might know probably just about as well as anyone how much money he made over his career.

I signed Antoine Walker out of school. Rick Pitino recommended us to Antoine in 1996, and one of my partners, Mike Higgins, worked for him for 10 years. It sort of breaks your heart, because most of these players come from extremely modest backgrounds. They have a very unique skill that they are able to translate into enough money that should last for a dynasty. There’s a thing called a dynasty trust, where you can take care of your family for multiple generations. And it’s sad. It’s nothing you want to criticize. You want to cry for him, or pray for him, because he’ll never see that kind of money again.

What I think is that athletes have the unique ability, when you’re making $100-plus million dollars, to impact a lot of situations charitably. Dikembe Mutombo is a role model who built a hospital in the Congo with $20 million of his own money. Antoine Walker made approximately what Dikembe made, and what’s his impact? What’s he going to be remembered for? Mutombo is going to be remembered as a humanitarian; he’s going to be remembered for the hospital; he’s going to be remembered for the finger wag, but he’s made an impact on society. People like Antoine could have made an impact in Chicago. He could have donated money for an athletic facility at his high school; he could have given money to inner city education, and instead, he’s going to be remembered for going bankrupt. It sort of fosters all the negative stereotypes of athletes, as overindulgent. And Antoine’s not a bad guy, but it saddens me greatly.

With highly publicized cases like that out there, have players started to ask you early on for more advice in terms of managing their money?

I don’t wait for them to ask. I think, to be an agent, you have to be proactive. I don’t wait for my clients to ask. From day one, take Evan Turner for example. We’ve been talking about this probably before I even signed him. From the first day I met him, I told him how important this is. He’s going to make a lot of money. What is he going to have to show for his career? A couple of old shoes, a few hats, T-shirts? What is he going to have to show for it? I think of the greatest accomplishments that Michael’s had, which was my dream the day I signed him to his first deal with Nike. The first deal was Air Jordan, but it wasn’t Jordan Brand. Jordan Brand didn’t come into existence until much later.

I told him when he was 21-years-old that my dream was that he would get married, have kids, and if he was lucky enough to have a son, his son could walk into a Foot Locker when he was 14 and buy a pair of Air Jordans. That was in 1984. Obviously he has two sons, Marcus and Jeffrey. Jeffrey is 22, and at 22, he can still walk into Foot Locker and buy a pair of Air Jordans. What is your legacy? What are people going to remember about you, other than the fact that you were a great player? And the financial wherewithal that these players have gives them a chance. In my own career, a lot of people remember me for different deals I made, or being tough, or whatever, but I have my own college now at Syracuse University, the David B. Falk Center for Sport Management. My wife and I could not be more proud. When people don’t know who I was, whether I was an agent or a doctor, I am going to have a building in my name, and a program. That’s something that I’m particularly proud of.

I told him when he was 21-years-old that my dream was that he would get married, have kids, and if he was lucky enough to have a son, his son could walk into a Foot Locker when he was 14 and buy a pair of Air Jordans. That was in 1984. Obviously he has two sons, Marcus and Jeffrey. Jeffrey is 22, and at 22, he can still walk into Foot Locker and buy a pair of Air Jordans. What is your legacy? What are people going to remember about you, other than the fact that you were a great player? And the financial wherewithal that these players have gives them a chance. In my own career, a lot of people remember me for different deals I made, or being tough, or whatever, but I have my own college now at Syracuse University, the David B. Falk Center for Sport Management. My wife and I could not be more proud. When people don’t know who I was, whether I was an agent or a doctor, I am going to have a building in my name, and a program. That’s something that I’m particularly proud of.

A player like Evan Turner is a rare instance of someone who is kind of known for staying above board with recruiting and things in his basketball career, and you are known as someone that doesn’t deal in that area. What do you think about the world of AAU and the investment sneaker companies put into these programs?

Honestly, I find it amusing. Without being overly cynical, they spend all this money for these players, but when they finally come out to the pros, if you don’t pay them top dollar, you’re not going to keep them. I had this discussion with Li-Ning. We were discussing whether they should get involved in grassroots basketball. There are a lot of stories right now that they are getting involved with Sonny Vaccaro, who is sort of like the godfather of grassroots basketball. First of all, I think what worked in the 1980s for Nike, when Nike was a small company, wouldn’t necessarily work for someone in 2010 any more than asking why don’t LeBron and Kobe sell a billion dollars like Michael does. It doesn’t work the same; you have to try something a little different.

If I look at it historically, James Worthy wore Converse his whole career at Carolina, three years, was the number-one pick in the draft, and signed with New Balance. Michael was the next player out, played in Converse for three years, wanted to sign with adidas, and signed with Nike. The next year, Patrick came out in 1985. He wore Nikes all through high school and college, and he signed with adidas. Allen Iverson wore Nikes all through high school and college, and he signed with Reebok. Those are four top-50 players, and Hall of Fame players. I could go on and give you a lot more examples. Elton Brand wore Nike at Duke; now he’s wearing Converse. I think that when the players come into the pros, they want certain marketing commitments. Regardless of what they wore in high school, junior high, or even college for those that went to college, they want those kinds of things. And I think that the amount of money they spend on the AAU programs to build “brand loyalty” amongst the young guys, for the superstars, 95 percent of the time is not going to work. Occasionally it will work. The story is that Kevin Durant stayed loyal to Nike, and I respect him for that. I’m a big Kevin Durant fan, and I think he’ll be the best player in the League in the next 12 months. There’s a rule in basketball that people like me who represent players can’t represent management. You can’t represent pro coaches, pro owners or pro general managers. If the NCAA passed a similar rule with the shoe companies saying you can either have college teams or AAU teams and you can’t have both, and the shoe companies pulled out of AAU, I think it’d dry up in two years. I really believe that.

Do you think it would be a good thing for AAU to disappear?

I think that there’re benefits of AAU basketball. I think it keeps kids off the streets in the summer. But I think it’s like any pendulum that’s gotten out of control. I think the kids play way too many games; they get used to losing way too many games. The style of play tends to promote individuals rather than teams. You sort of have SportsCenter players that want to be in the highlights every day. And so I think there’re some good things about it, but I think it’s really diminished the role of the high school coaches, and sometimes, I think it’s really diminished the role of the college coaches. It’s become really powerful, and I think the reason it’s powerful is because of the funding from the shoe companies. If you really look at what Sonny did at Nike in the early days, it was revolutionary, and I give him a lot of credit. He signed a lot of the college coaches when they didn’t have deals, and he created sort of the whole AAU network. Then he went to Reebok. Did it work as well for Reebok 15 years later? No. Then he went to adidas. Did it work as well for adidas? Adidas and Reebok today, their combined market share in basketball, I think, is four percent. So how well did it work? And if he turned around and went to Li-Ning, or Anta, or some new company today, I don’t think that approach is going to have the same efficacy today. When you are on your fourth or fifth company, after a while, I think it gets diluted.

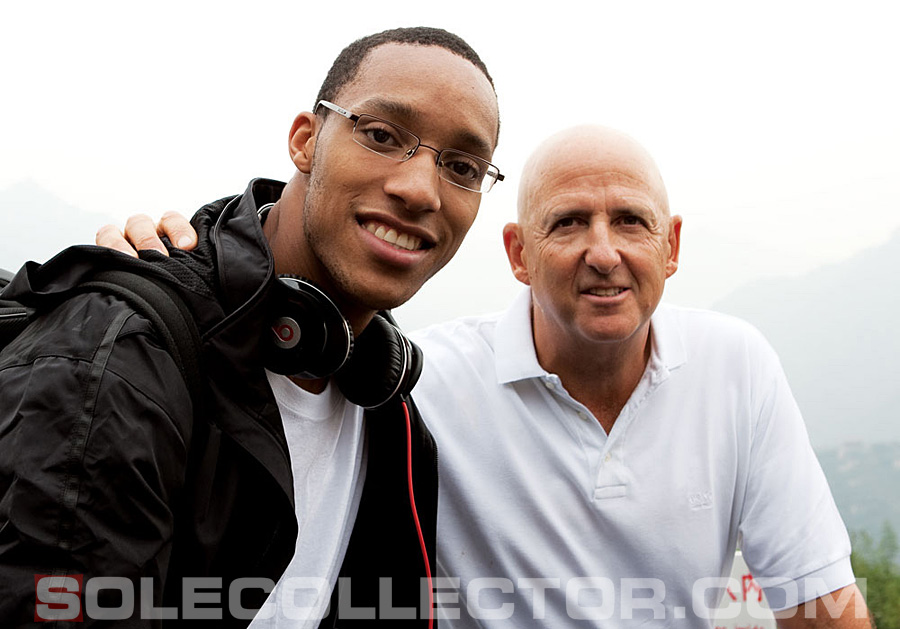

Above: David Falk helping Evan Turner on the set of his very first Li-Ning photoshoot.

Do you have any stories of “disagreements” you and MJ might have had along the way over endorsements?

Oh, sure. Obviously, you don’t have relationships where you don’t have disagreements. Michael is an extremely bright, independently minded person. And I’m an extremely stubborn, [laughs] passionate person. I’ve told this story a million times. When he got involved with his gambling situation, and the story broke, I remember watching a game, and when the game ended, he got interviewed, and he was wearing sunglasses in the locker room. This isn’t Stevie Wonder, this isn’t Dennis Rodman, this is Michael Jordan. I flew out to Chicago right away. When I picked up the paper, I remember reading a quote from Jessie Jackson – this was at the very height of his power back then – and he was saying that Michael Jordan can associate with whomever he wants. No one can tell him who to associate with. I cringed. So I sat down with Michael, and I said, “Look, you haven’t robbed a bank; you haven’t killed someone; you haven’t committed a serious crime, or any crime. But you made a mistake in judgment. You hung out with people that have embarrassed you. What you should do is apologize.” He got really, really upset with me, and he said, “I knew you were going to say that. You always support the companies.” I said, “No, I’m not supporting the companies; I’m supporting you. You have a simple choice to make. If you want to be a role model, and you make a mistake as a role model, you need to come clean, fess up, and say you made a mistake in judgment. If you want to hang out with who you want to hang out with, that’s cool, too. Let’s cancel all the contracts, and you have free reign. You can hang out with drug dealers; you can hang out with pimps; you can hang out with whomever you want to. Don’t worry about what people think, because you don’t want to be a role model. But you can’t be both.”

It’s the only time in my career that I was really worried that he would fire me. When you get into those kinds of situations, I’m not trying to be a tough guy; I’m not trying to be confrontational; I’m not trying to impress him. What I’m really trying to do is do my job. I’m trying to do what I think is right and give him the best advice I think I can, and not be intimidated by the fact that he’s Michael Jordan. You hope that after all the years of working together that he trusts you enough to know that you are telling him this because it’s what you believe. You’re a doctor, and your prescription is the next course of action for treatment of the problem. That night after the game, he did interviews, and he apologized, and it diffused the situation. I never said another word about it. I never said, “Thanks.” He never came to me and said, “Thanks.” He didn’t have to say thanks, because saying sorry was his way of saying, “Thanks. You stood up to the test, and you gave me good advice, and I appreciate it.” Staying with me his whole career was the best thanks he could have ever given me.

The same thing happened with John Thompson; I had the identical situation with him over the issue of Patrick Ewing coming out of school as a junior. He wanted him to come out; I wanted him to stay. John Thompson is an extremely powerful individual and someone that is my hero in life. I’ve said that publicly numerous times. You want your client to know that no matter how much pressure they put on you, you are going to give them your best advice. They may not listen to your advice. They might say, “Thanks a million, but I’m not saying sorry to anyone,” or “Thanks a million; Ewing’s coming out of school.” I’m the advisor; I’m not the principal. All you can do is give your best advice. If your doctor tells you, “Zac, if you don’t lose 20 pounds, you’re going to have a heart attack,” you might say, “Doc, forget it, I’m not going to lose weight. I love eating Big Macs.” But if he’s your doctor, you want him to tell you what he really thinks. At an early age, maybe because I was so young with both Michael and John, I always felt that I wasn’t like I am now at 60, where I can say I’ve been doing this for 35 years, and I can be a little more relaxed. To an Evan Turner, he knows I’ve done it for Michael and Patrick and all those guys, but when I was 33 and in just the early part of my career, I always felt that I had to show them that I wouldn’t be intimidated by my own clients or be afraid to give them the best advice. I think too many agents today are just yes-men. They just tell the players whatever the players want to hear, because they are afraid they will get fired. You can’t coach basketball like that. Doug Collins can’t say to Evan, “How do you want to play? Do you want to play point guard, or two, or three? Do you want to play up?” He’s the coach. He’s been there and coached great players. He’s going to tell Evan Turner how he wants him to play. And Evan is going to have to look at Doug and respect him enough to know he’s been there and done it. He’s had great players before him. And that’s how I feel as an agent. You’ve got to have the confidence to give your client the best advice.

The same thing happened with John Thompson; I had the identical situation with him over the issue of Patrick Ewing coming out of school as a junior. He wanted him to come out; I wanted him to stay. John Thompson is an extremely powerful individual and someone that is my hero in life. I’ve said that publicly numerous times. You want your client to know that no matter how much pressure they put on you, you are going to give them your best advice. They may not listen to your advice. They might say, “Thanks a million, but I’m not saying sorry to anyone,” or “Thanks a million; Ewing’s coming out of school.” I’m the advisor; I’m not the principal. All you can do is give your best advice. If your doctor tells you, “Zac, if you don’t lose 20 pounds, you’re going to have a heart attack,” you might say, “Doc, forget it, I’m not going to lose weight. I love eating Big Macs.” But if he’s your doctor, you want him to tell you what he really thinks. At an early age, maybe because I was so young with both Michael and John, I always felt that I wasn’t like I am now at 60, where I can say I’ve been doing this for 35 years, and I can be a little more relaxed. To an Evan Turner, he knows I’ve done it for Michael and Patrick and all those guys, but when I was 33 and in just the early part of my career, I always felt that I had to show them that I wouldn’t be intimidated by my own clients or be afraid to give them the best advice. I think too many agents today are just yes-men. They just tell the players whatever the players want to hear, because they are afraid they will get fired. You can’t coach basketball like that. Doug Collins can’t say to Evan, “How do you want to play? Do you want to play point guard, or two, or three? Do you want to play up?” He’s the coach. He’s been there and coached great players. He’s going to tell Evan Turner how he wants him to play. And Evan is going to have to look at Doug and respect him enough to know he’s been there and done it. He’s had great players before him. And that’s how I feel as an agent. You’ve got to have the confidence to give your client the best advice.

Do you have a player that you most regret not being able to sign, from the standpoint that you could have really helped them in their career?

The one player that I really like, and I’ve always liked him, is Grant [Hill]. He was from Washington, D.C. and had a great family. His dad went to Yale and played for the Cowboys. I was a big Cowboys fan; I loved the backfield of Duane Thomas, Calvin Hill and Roger Staubach. His mom went to Wellesley, and she’s a very successful businesswoman. He went to Duke, and we represented Coach K. He’s just a delightful person, classy and good-looking. I think that 10 years after Michael, we had a level of knowledge for a player of Grant’s caliber that could have taken him to a different level. Now, has his life changed because he didn’t choose me? No. Has my life changed because he didn’t? No. But I say, unabashedly, that as a man, I really, really like Grant Hill. I like his dad immensely. If there’s one that got away, I say he’s the one. The other guy that got away, and it’s just the nature of the business, was David Robinson. We had met David Robinson; he’s another really classy guy with a great family. There’s always a question that comes up in, if I can use the word, “recruiting.” You know it’s the question. It’s a really important question, and you know what answer the player wants you to give them. If you give them the answer they want, you’ll probably sign the player. And I guess I just have a very stubborn streak, but I’m never going to lie. David’s question was, “Can you get me out of the Navy?” And we said, “No.” We had a lot of contacts politically. A former partner of mine, and a guy I used to work with, I don’t think gave him the same answer, and he went with that guy, and served two years in the Navy [laughs]. If I had it to do again, I’d give him the same answer.

I had that with Desmond Howard when I met him at Michigan. We had him; his advisor wanted him to go with us. His question was, “Where will I go in the draft?” The guy just won the Heisman Trophy, and you know he wants you to tell him, “You’re going to go number one.” But I knew he wouldn’t go number one. I told him he’d go four to six. He picked my good friend Leigh Steinberg, and what number did he go? He went number five, to the Washington Redskins, in my back yard. You get those questions all the time. I believe, without getting religious, it’s like being Job. It’s a test of your character. Can you live with the disappointment of losing a player you want to get because you are going to stick to your values? I don’t want to get a player if I have to lie to them; I don’t want to get a player if I have to buy them. That’s not the way to start a longterm relationship. Because, one day, when the player asks you the kind of questions that John Thompson asked me about Ewing, or Michael Jordan asks you about gambling, and you look them in the eye and say what you really think, they have to know that you are really being straight.

You sold your company in 1998, and really slowed down as far as being in the agent business. What made you want to step back in a little more like you are now? What’s in it for you at this point, and what’s different?

You sold your company in 1998, and really slowed down as far as being in the agent business. What made you want to step back in a little more like you are now? What’s in it for you at this point, and what’s different?

I sold it for a number of reasons. One, it was a tremendous opportunity for my family to get long-term security. I never believed you could even sell a personal services business like this. And we also saw that the winds were changing. A lockout was imminent. We knew the rules were going to change; I didn’t know they were going to change the way they’ve changed. And I’ve never looked back. It was a great opportunity for me. What happened as a result of the sale is that the gentleman who bought our company, Robert Sillerman – who is a brilliant guy that I’ll always be grateful to for giving me this opportunity – he wanted us to grow the business. We went out and bought something like 14 other agencies. We bought three big baseball agencies; I bought my largest competitor, Arn Tellem, who was always the individual that I had the most respect for in this business. We bought a football company with Jim Steiner and Ben Dogra. Ben’s probably the most successful young agent in football right now with Tom Conda at CAA. And at one point, as the chairman of the sports group, I think we had something like 900 employees and 1,100 clients, and it wasn’t fun for me working for a very large company. When SFX sold to Clear Channel, and you are a public company, there are a lot of restrictions, and you have earnings reports to show. You are trying to blend all of these different personalities from their own small agencies into a big agency, and there was a lot of resistance. People weren’t as willing to meld themselves into the culture I was trying to create. Maybe I wasn’t a great manager. So I stepped down, and for seven years, I didn’t sign any rookies. I signed only one player in Sam Cassell.

I really didn’t want to sign rookies. I saw the way it was going, and a lot of these players came to college, and they already had agents from high school. There were large-scale financial inducements for players to come out. It really made me sick. It didn’t make me mad. I was disappointed. I looked and said, “I had my run. I had a great run.” And like a player, you have to know when to walk away from the game. You don’t want to be a punch drunk fighter getting your head bashed in. The last rookie that I’d personally worked with was Elton Brand in ’99, but I’d signed Darius Miles in 2000, who was the highest drafted high school player of all time at that time. So, I went seven years without a rookie. Then, Coach Thompson III invited me to meet Jeff Green. People who know me know I love Jeff Green. He’s a special guy for me. He’s sort of my first player in round two, if you will. At that point in my career, I did it because I felt I had all this knowledge that I had acquired over a 35-year period. What was I going to do with it? You’re not going to sit at home and use it. You’re not going to use it on the golf course. I’d used it a little bit teaching, but I signed Jeff Green, and he really reinvigorated my career. I thought Elton would be my last legacy guy; I’m very close with Elton as well. But, a little bit like Evan did this past year, Jeff Green was the first player in round two to make me realize that you can still sign great players who are good people, and clean. You may not be able to sign a lot of them [everyone laughs], and I don’t want to sign a lot of them.

Right now, I have nine clients. Three of them are older guys – Juwan Howard, Mike Bibby and Elton Brand – who were between ’94 and ’99, and the rest of them have come after 2007. At some point in time, Juwan, who I love to death, is going to retire. I told him he’s got to chase Mutombo’s record, so he’s got about another 10 years. [laughs] And Mike’s going into his 13th season, so I’m going to end up with five or six more young players. I want to have 10. When I have 10, my intention is to cut it off. I think I have room for five more first-round picks. I want to really be selective about who those guys are. Those are players that I plan to personally work for. I’m not going to hand them off to a junior guy. I don’t have runners who work for me. It’s me, and I have an assistant named Danielle Cantor, who’s been with me for 10 years and is very talented. And I’m doing it because at this point in my career, I look at myself more as a teacher, and I think I have a lot to transmit to a young Jeff Green or young Evan Turner. I have my college at Syracuse, so I try to go up once a month and teach, and I have my clients. In an era where there’re wage scales and maximums, and your role as a negotiator is really limited, I want to be more of a teacher. And when I look at someone like Evan, what really is rewarding to me is the fact that I was asked by his family at the end of his sophomore year if he should come out. I told them, no, he wouldn’t go in the top 20, and that he’d go in the top eight as a junior. I told them that if he worked really hard, he had a legitimate shot at being Player of the Year. He goes back to school, gets hurt, comes back, becomes Player of the Year, and gets drafted number two. That validates me, in my own mind. I gave the guy really good advice -- I was the only person that told him to go back. It wasn’t like two-to-one, or three-to-one; no one told him to stay. But for Evan Turner, it was the perfect advice. That’s what my motivation is. Do I enjoy making the Li-Ning deal? Sure. I enjoy being a little bit of a maverick and sort of bucking the trends. I enjoy that. But I want to be a good teacher.