words, interview & images // Zac Dubasik

as published in Issue 45 of Sole Collector Magazine, the 10th Anniversary Issue

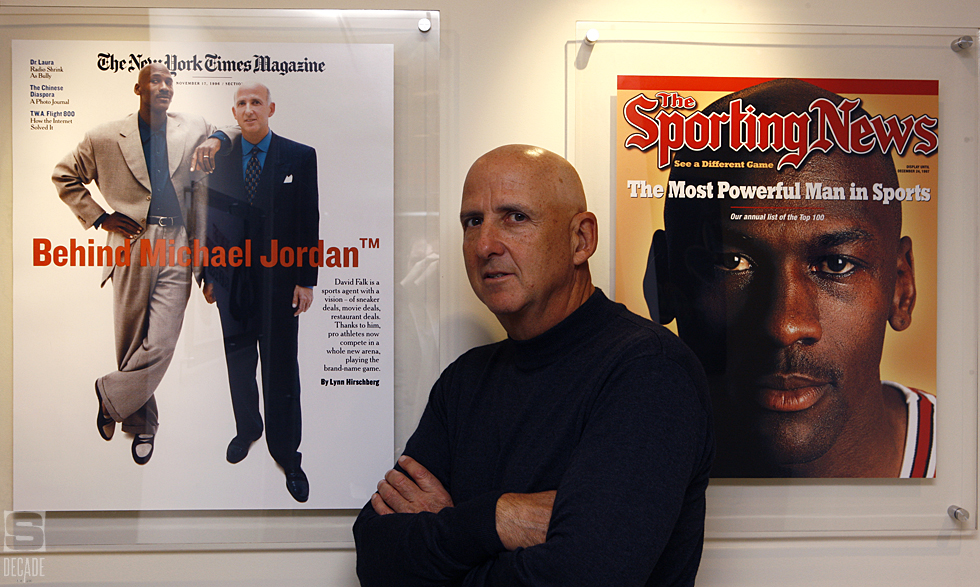

In Issue 36, we sat down for an interview with legendary agent, David Falk. It was Falk, as MJ’s agent, who brought Michael Jordan and Nike together back in 1984. Falk gained a reputation as one of the most powerful individuals in sports, not only through marketing deals like these, but also by negotiating landmark NBA deals, like multiple then-highest-in-the-League contracts, and the first $100 million deal in all of sports.

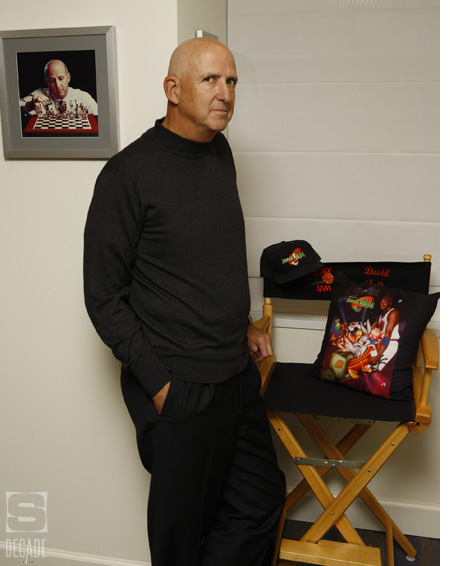

After meeting Falk in the summer of 2010, while traveling to China for Evan Turner’s first trip to Li-Ning, we later caught up in his D.C. office for an extensive interview. here are highlights.

Excerpted from Issue 36. You can read the full interview here: Part 1 / Part 2

Zac Dubasik: So, obviously, the client you are most known for is MJ. Could you talk about how that came about?

David Falk: What happened at North Carolina was our firm, ProServ – Donald Dell and a gentleman named Frank Craighill, who were the two senior partners – had a very close relationship with Coach Smith. Frank Craighill had been a Morehead Scholar, which is like a scholar athlete at Carolina. And so they had represented George Karl, Dennis Wuycik and Bobby Jones in the old days. Then it really sort of clicked in about ’77.

We represented a player named Tommy LaGarde, who had busted up his knee, and they got him a great deal at number nine. That was one of the deals I was actually involved with. So, from that time on, we basically got all the Carolina guys. We got Phil Ford, who was the Player of the Year in ’78, Dudley Bradley in ’79, Mike O’Koren in ’80, Al Wood in ’81 and Worthy in ’82. So the players, after a while, they sort of learned what I call “the drill.” The drill was, we’d come down to Carolina, Donald and myself – he was the senior guy, I was the junior guy – and the players knew that Donald would do their first deal. They called him the ghost. They’d never hear from him again. And then I would take over and do all the grunt work, and then when the second contract came, I would do it.

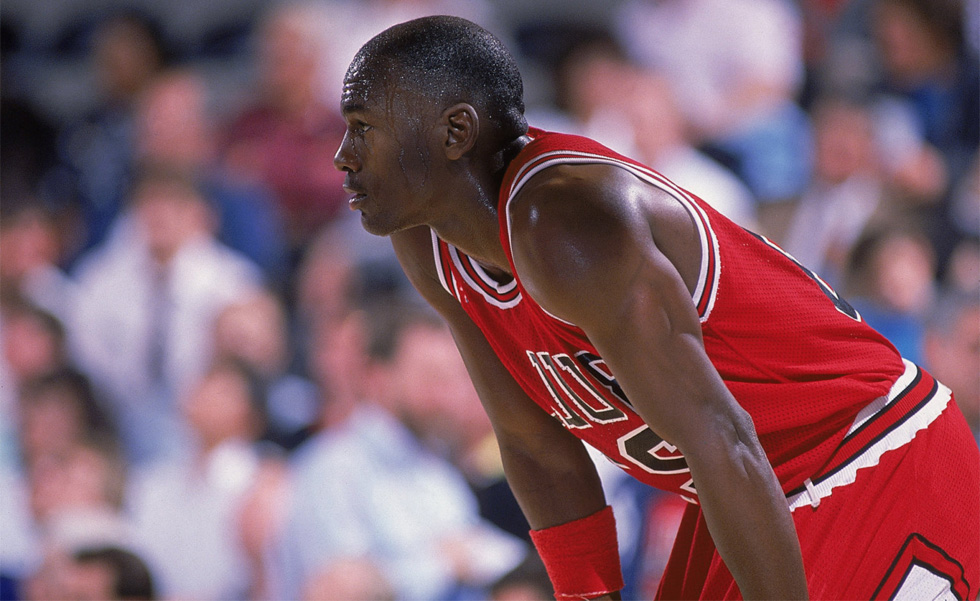

By the time Michael came out of school in ’84, we went down to make a presentation. There was no recruiting allowed then. Dean didn’t allow any recruiting whatsoever. And when I say whatsoever, underline the “ever.” [Laughs] He’d say, don’t call them, don’t call the parents, don’t “bump” into them, and you’ll have a one-hour presentation at the end of school. So, Dean recommended to Michael that he leave school as a junior. We went down and met him. He knew "the drill," and he signed with us.

Clearly we were invited down on the strength of Donald’s relationship. I would never dispute that. Donald did his first contract with the Bulls; I had no involvement with it whatsoever. And that was the only deal that he was involved with. After that, I took over and developed a very close relationship with Michael. I felt that Michael needed to know that I was working for him. I wasn’t working for a company that represented him. I was working for him. I would try to recommend things to him, and screen things for him, to promote his interests. There were a number of occasions in the first four or five years when his interests sort of collided with the firm’s interests.

ZD: Do you have any examples?

DF: There was one situation where Donald had come up with an idea for Michael to play Magic one-on-one, for a made-for-TV special. It was a very interesting idea, but Michael didn’t want to do it. And when I told Donald that Michael wouldn’t do it, he got very upset and asked who I was working for. I said, “I’m working for Michael. The day he doesn’t think that I’m working for him, he’s going to fire us.” Because, at that level, you need to know that someone is there 100 percent for him. Today, my former partner, Curtis Polk, took over his representation when Michael became an owner. Agents aren’t allowed to represent owners and players at the same time. And that’s what you need to know.

You need to know that your advisor is 100 percent going to tell you what they think is in your best interest. After my second or third year working for Michael, he actually asked me to leave ProServ and go to work for him full-time. I really wanted to do that. For one thing, I really wasn’t being paid very much money by Donald, and it was obviously flattering for the best young player in the game to ask me to do that. But I guess I wasn’t confident enough in myself. I worried that if he got mad at me and fired me, I’d be out of the business. [Laughs] So, I passed. But I think over the first four years, I earned Michael’s trust.

For the Air Jordan deal, I came up with the name “Air Jordan.” I had an extremely close relationship with Rob Strasser at Nike, who was the head of marketing, and I did all the deals. I wouldn’t let anyone in the firm do any deals, in any sport, for Nike yet. I understood what they wanted, what their MO was, and maintained that relationship. Donald had a very close relationship with adidas, and another gentleman in the firm, Lee Fentress, had a very close relationship with Converse. I was the young guy; I was looking for my own identity. I sort of found Nike when they were very small and grew with them. So, Michael came to Nike because of my relationship with Rob Strasser.

ZD: You've mentioned that Michael is the only person to be a brand, but do you think there is still value in giving big deals to a Kobe or LeBron?

DF: Absolutely. Tremendous value. But I think you have to understand that there’s a difference between being a brand and being an endorser. I think that if you look at someone like Tiger, for example, I’m not sure that if you study how much product Tiger sells of Tiger Woods clothes that it’s been really amazing. But if you look at what Tiger’s done for the Nike Golf brand – he took a company that wasn’t even in golf and legitimized them by himself, and the sales have been phenomenal. So, you can say Tiger has been an incredibly effective, impactful endorser for Nike, but not as incredible and impactful at selling the TW brand and the logo.

And that’s not a knock; I just think Jordan is a fluke. It’s not that he’s better; I think he came along at a time when there was no one else doing it in team sports. He was a star on a worldwide stage in the Olympics in 1984, and no one expected him to do it. If you look at the chronology of stars in my world, 10 years after Michael was Grant Hill. He should have been the next guy. Properly marketed, I think he could have been the next guy. Nine years after Grant, almost a decade later, was LeBron. I’m a big LeBron fan. I think LeBron’s popularity has taken a big hit with "The Decision," but it’ll come back, because they are going to win, and he’s a great player. I think he has a real chip on his shoulder to prove to people that it was a good decision, even though it might not have been well implemented. I’m just disappointed. And I’ve told this to Aaron Goodwin, who was his first agent; I’ve told this to Maverick Carter, who is his second agent, to raise the bar. You need to do in 2010 what Jordan did in ’84. To go with McDonalds, Nike, and the exact same product mix 25 years later is not exactly breakthrough. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with it; it’s just not what you’d expect for a guy that coming out of high school [that] you know is going to be a prodigy.

ZD: Do you think it’s just a case of those companies being so well established and writing the biggest checks?

ZD: Do you think it’s just a case of those companies being so well established and writing the biggest checks?

DF: No. I just think it’s going to require someone who’s the brand manager for the Bryant brand, and the James brand, and the Durant brand to break the mold and do something different.

ZD: What do you think when you see a guy like Antoine Walker, for example, who you know probably just about as well as anyone how much money he made over his career?

DF: I signed Antoine Walker out of school. Rick Pitino recommended us to Antoine in 1996, and one of my partners, Mike Higgins, worked for him for 10 years. It sort of breaks your heart, because most of these players come from extremely modest backgrounds. They have a very unique skill that they are able to translate into enough money that should last for a dynasty. There’s a thing called a dynasty trust, where you can take care of your family for multiple generations. And it’s sad. It’s nothing you want to criticize. You want to cry for him, or pray for him, because he’ll never see that kind of money again.

What I think is that athletes have the unique ability, when you’re making $100-plus million, to impact a lot of situations charitably. Dikembe Mutombo is a role model who built a hospital in the Congo with $20 million of his own money. Antoine Walker made approximately what Dikembe made, and what’s his impact? What’s he going to be remembered for? Mutombo is going to be remembered as a humanitarian; he’s going to be remembered for the hospital; he’s going to be remembered for the finger wag, but he’s made an impact on society.

People like Antoine could have made an impact in Chicago. He could have donated money for an athletic facility at his high school; he could have given money to inner city education, and instead, he’s going to be remembered for going bankrupt. It sort of fosters all the negative stereotypes of athletes as overindulgent. And Antoine’s not a bad guy, but it saddens me greatly.

ZD: With highly publicized cases like that out there, have players started to ask you early on for more advice in terms of managing their money?

DF: I don’t wait for them to ask. I think, to be an agent, you have to be proactive. I don’t wait for my clients to ask. From day one, take Evan Turner for example. We’ve been talking about this probably before I even signed him. From the first day I met him, I told him how important this is. He’s going to make a lot of money. What is he going to have to show for his career? A couple of old shoes, a few hats, T-shirts? What is he going to have to show for it?

I think of the greatest accomplishments that Michael’s had, it's his brand, which was my dream the day I signed him to his first deal with Nike. The first deal was Air Jordan, but it wasn’t Jordan Brand. Jordan Brand didn’t come into existence until much later. I told him when he was 21-years-old that my dream was that he would get married, have kids, and if he was lucky enough to have a son, his son could walk into a Foot Locker when he was 14 and buy a pair of Air Jordans. That was in 1984. Obviously he has two sons, Marcus and Jeffrey. Jeffrey is 22, and at 22, he can still walk into Foot Locker and buy a pair of Air Jordans.

What is your legacy? What are people going to remember about you, other than the fact that you were a great player? And the financial wherewithal that these players have gives them a chance. In my own career, a lot of people remember me for different deals I made, or being tough, or whatever, but I have my own college now at Syracuse University, the David B. Falk Center for Sport Management. My wife and I could not be more proud. When people don’t know who I was, whether I was an agent or a doctor, I am going to have a building in my name, and a program. That’s something that I’m particularly proud of.