1.

In Bret Easton Ellis' novel American Psycho, the psychotic narrator Patrick Batemen muses, "Each model of human behavior must be assumed to have some validity. Is evil something you are? Or is it something you do?" While he spends most of the book either describing peoples' outfits or brutally torturing them, this meditative moment manages to spawn a couple of interesting questions. Like most human beings, I have often pondered the "root of evil." In spite of common wisdom, I've decided that it's not money based on my refusal to define apples as currency. For one thing, they do grow on trees, and I know for a fact that you can get them free in hotel lobbies. Yet, by the same token, I know that money can make us do mysterious things.

When you're in the second grade, the concept of money is just catching up with the concept of wanting stuff. As I've grown older, I feel that this connection has actually dissipated. When I buy a song on iTunes and it immediately shows up in my music library, I am completely convinced that no money has changed hands. Though they email "receipts" that say things like "Slayer 'Angel of Death' $0.99. Nickelback 'How You Remind Me' $0.99. Bill Withers 'Lean On Me' $0.99," I look at these as mildly amusing practical jokes. But when you're in second grade, you deal only in hard cash and those paper tickets you get from Skee-Ball machines at Chuck E. Cheese's—five-hundred yellow tickets translate roughly into a Chinese finger trap and Whoopee Cushion. The tangible immediacy of this commercial exchange avoids the abstract concepts of "electronic transactions" and "credit cards."

When I was in second grade, I spent most of the money that came into my hands on trading cards. My allowance did not fund big-ticket purchases like Nintendo games and Lego fortresses, and "saving" money didn’t fit into the immediacy of the cash-for-stuff economic model ingrained in my young brain. Sometimes I would buy candy, but once I accidentally bought Halls thinking that "lozenges" was an adult word for delicious sweets. Needless to say, I was sorely mistaken. After that, I almost always bought cards.

Back then, my bedroom closet was full of meticulously arranged shoeboxes and trapper keepers full of trading cards, as well as one Perrier Juoet aluminum case which I must have pilfered at the tail end of a dinner party while playing "Spy-O-Matic." Spy-O-Matic was a game I invented in which my brother, my friend Will, and I would assault our elders by detonating stink bombs in their general vicinity. In retrospect, its objectives were more suited to the dossier of a terrorist than a spy, but we cared little for these distinctions. The main objective was to use a combination of stealth and foul smells to incite mayhem.

But when it came to my card collection, order and precision reigned supreme. The cards I collected were baseball, basketball, and football; they were categorized first by sport, then by team and position. I even had a special section for "mistakes," like a card I had that said "Tim Brown" but featured a picture of a different player. At the time I found this hilarious, but now I just find it unprofessional.

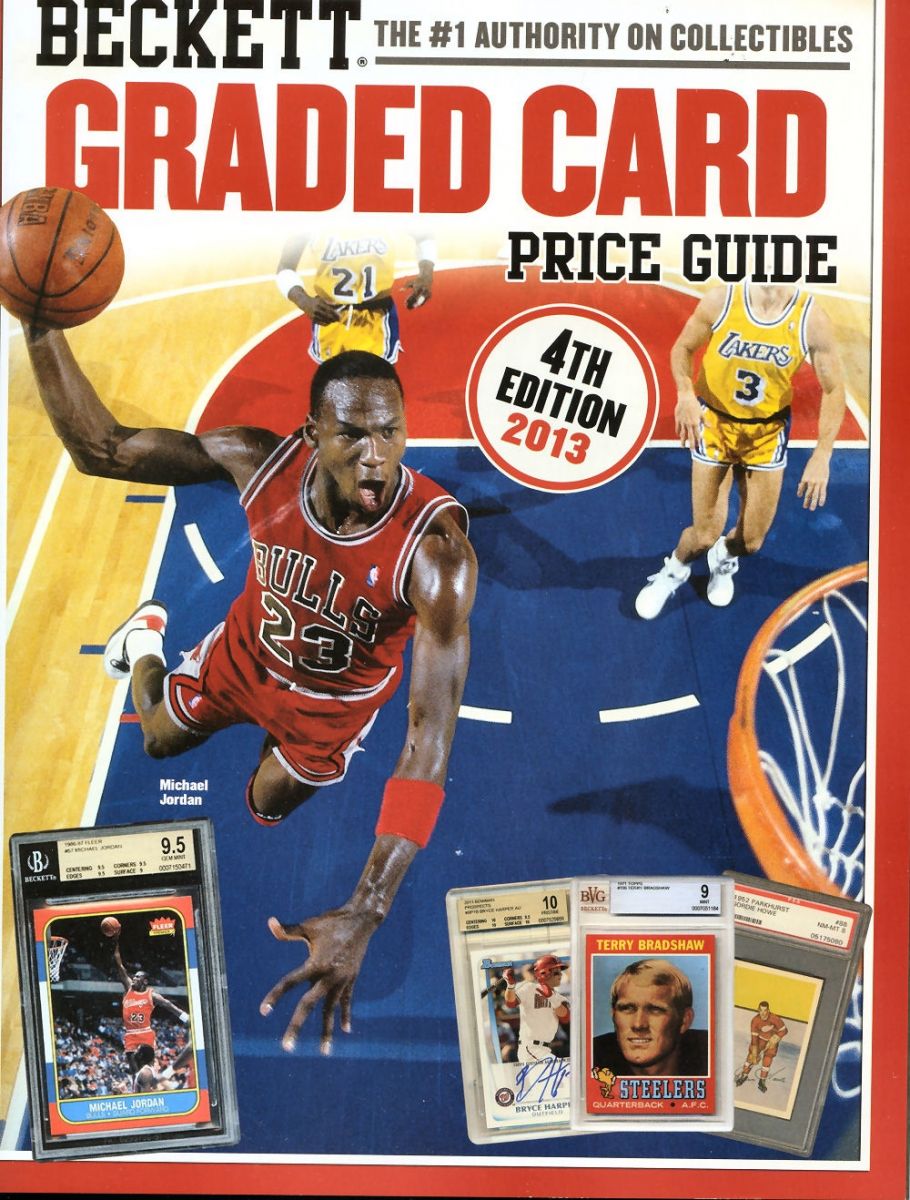

One day I decided that I should re-organize the cards by value, but this endeavor took so long that by the time I finished, a new Beckett was published with different prices. At that point, I just lost heart and reverted to the old method, which also took ages. But the reason I wanted to categorize the cards by value was because I had started a side hustle to supplement my allowance: with no other recourse for acquiring Nintendo games beyond birthdays, Christmases, and bouts of influenza, I started selling cards with my partner-in-crime, Audrius.

As his name would suggest, Audrius was slightly odd; he wore a head of long shaggy hair and spent his formative years traveling through Africa with missionaries. The first and last sleepover I had at his house involved watching Child's Play, microwaving a tomato until it exploded, and performing a choreographed dance to a Jackson 5 song for his extended family. We woke up at 5am and he asked me if I wanted to play basketball. I said "yes," but unfortunately he didn't actually have a basketball hoop so we just lurked around his neighborhood, playing in other peoples' backyards until they woke up and chased us away. All things considered, the sleepover was utterly terrifying.

On Wall Street they say that once you make your first sale, it's like the greatest rush you've ever felt in your life. On the streets they say that hustling is not a job, it's a religion. In fact, I'm not sure if anyone says either of these things, but one thing I know for sure is that my first sale fed some entrepreneurial fire burning deep within my impish soul. From the get-go, Audrius and I had only one client, but he was a good one for three main reasons: He was rich; he had practically no knowledge of sports; and best of all, he came to us. As we swapped cards and analyzed stats during lunch and break times, "Evan" (if that was his real name) would fester around us, watching hopefully. One day, he finally worked up the nerve to move in.

"Hey guys, can I get some of those cards?" he asked nervously.

"Well, what you got?" Audrius snapped back.

"I don't have any cards," he replied dejectedly, looking down at his too-clean Velcro sneakers. "But I've got some money?"

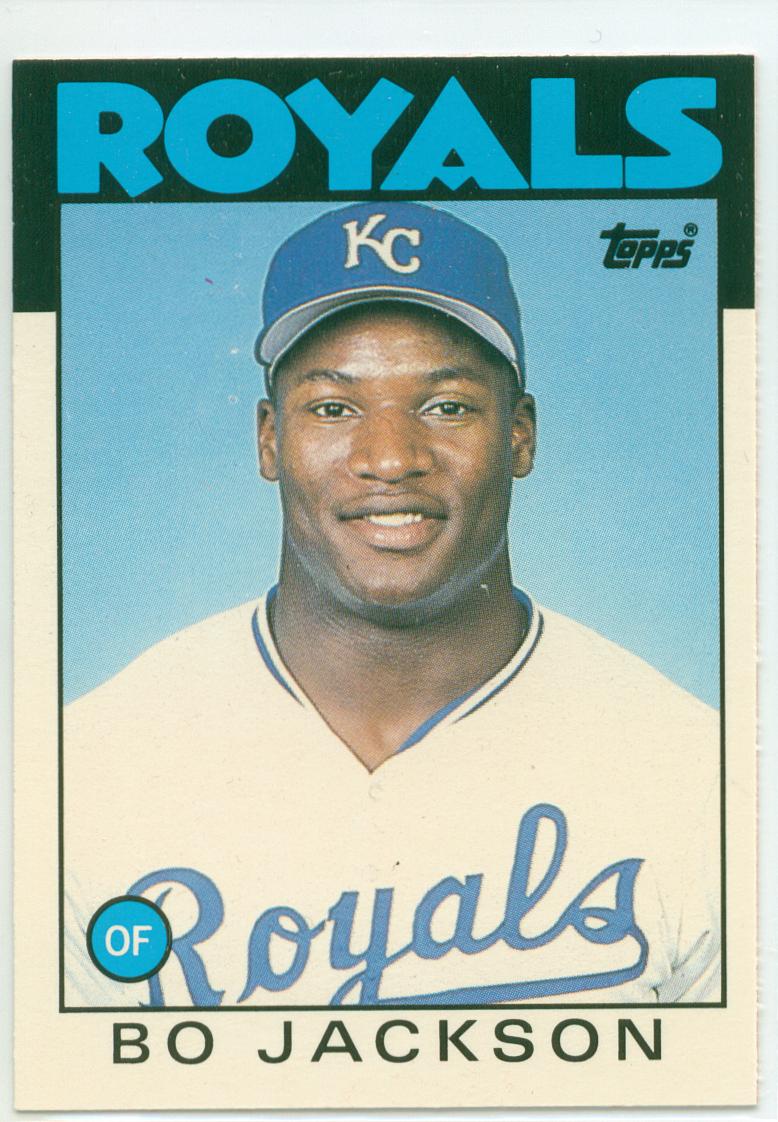

Before Audrius could speak, I swooped in for the kill. "Here's what I'll do for you, Evan…" I quickly shuffled through my stock and compiled a stack of throwaway cards and doubles. In order to maintain some semblance of value, I put a Bo Jackson card on top and told him that it was worth twice as much as a normal card because he played two sports. In retrospect, this was only partially false. (Outside the boys’ bathroom at school there was a poster of Jackson in a leather chair beneath the words, "Bo Knows Reading," which also worked in my favor.) Finally, I eyeballed the stack and placed it in a plastic carrying case.

"Twenty dollars," I said. He extracted a crumpled bill from his Osh Kosh B'Gosh corduroys and handed it to me. And just like that, I had a business. It was all instinct—a hustler's spirit, period.

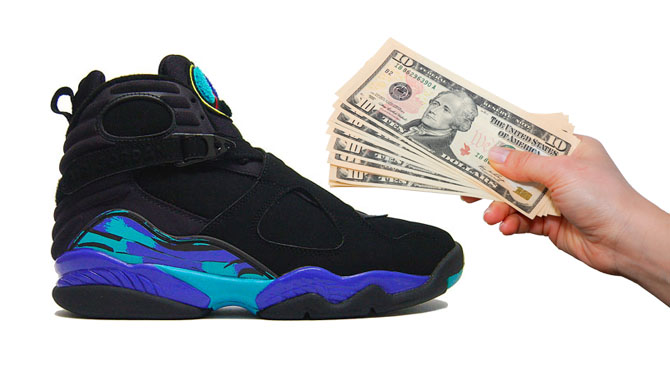

Because I was at that age when none of your pants have pockets, I had to tuck the twenty in between my other cards on the way out of school, arousing a suspicion in my au pair that she wisely decided to ignore so that she could spend more time doing Danish things. As time went on, the transactions quickened. Evan didn't even seem to look at the cards. He just handed over the money eagerly, and within the first month of business I had hustled my way to $150 in cold cash. I purchased a celebratory pair of Jordan VIIIs (the colorful ones with the criss-crossed strap across the laces—real hot). When queried about the source of my newfound wealth, I told my mom that I had found the money in the woods behind our house.

I didn't mind selling worthless cards to Evan. If he wanted to give me massive sums of cash in exchange for baseball cards that I didn't want, I wasn't going to stop him. I didn't even mind hiding the money from my au pair, because she once tricked me into ordering a bunch of WWF posters from the back of a magazine that never arrived. But lying to my mom filled me with a nameless dread that festered deep inside of me.

The fast money and gear to match came with a price tag that I never could have predicted. In the music video for "I Wish," the ghost of R. Kelly's mom asks her son, "What does it profit a man to gain the world and lose his soul?" That song was not yet out at the time, but this sentiment rankled clairvoyantly within me. I had sold my soul to the devil, and worst of all, the price was cheap. If the internet, let alone Ebay, had been available at the time, I probably could have gotten a better price.

My double life began to take its toll. While the "good little boy" sat at the dinner table and finished his leek-and-potato soup, the little devil within plotted maniacally. One night, my mom went out to a dinner party. I was not invited because, apparently, Spy-O-Matic had been disallowed at that particular household. When she returned, she found me crying uncontrollably in her bed, ready to let the truth out in one disjointed stream of garbled confession. For the most part, I blamed the whole thing on Audrius, who I think she was pretty distrustful of in the first place. She didn't get angry or punish me; instead, she said, "I never would have expected this from you," and left me to whimper in my room, staring into my closet. I leafed through one of the trapper keepers and found a Deion Sanders baseball card. Then I found a Deion Sanders football card, which was worth more. Yet they depicted the same person. How could one man carry two different values? My nine-year-old mind grappled with this quandary like a Rubik's Cube.

The next day, my mom called Evan's parents. Apparently, Evan had stolen over $500 from their "emergency fund," which they probably regretted hiding in their sock drawer. Together, the wise elders decided to stage a chaperoned meeting in which Evan and I were to exchange all goods that had changed hands and bury the hatchet once and for all.

To this day, the scene plays in my mind like a movie: On a dim autumn morning, we meet them outside on the walkway leading to our house. For some reason, we come out just as they are arriving—I'm not really sure why but I think it's probably irrelevant. Anyways, I march forward from the front door with my mother lagging about a half a step being me. Evan's mother drags him by the ear with a look of unrestrained fury. Evan looks down at the ground and says, "Here," as he hands me a shoebox with every card I had ever given him. I take it and said, "Here," as I hand him about 20% of the money he has given me, because I have spent the rest on the shoes and a pair of athletic shorts. The mother's exchange a few muffled words and then Evan's mom hauls him away, hassling and berating him, while my mom and I turn back to the house in silence. As the door closes, the market deterrent of motherly disappointment squeezes the spirit out of the young hustler, leaving a specter of the American Dream to soar depressingly over the closing credits.

Sometimes I tell myself I should be pleased that the moral low point of my life to date occurred in second grade. Since then, I've had a few slip-ups here and there, like the time I used my dog Biko as a scapegoat to cover up my defilement of our household, but never again did I pursue such a systematically unethical code of conduct as I did at the age of nine. Lurking among pairs of basketball shoes and oversized hooded sweatshirts, the prepubescent skeletons that I left in my closet that year still make me shudder.

Furthermore, the specter of the American dream—that fierce entrepreneurial spirit that flared up in such concentrated form, never to show its face again—still haunts the closet where I once kept my cards. It no longer has wings to fly, but it can never truly be killed, for it is not "of the flesh." As I think about this ghost of the past, I sometimes wonder where the profligacy of those days came from—was it something I did, or something I was?

In the song "I'm A Hustla," rapper and convicted coke dealer Cassidy brags, "In fifth grade I was hustling my Genesis games." Well, in second grade I was hustling my baseball cards. Could the streets have been mine? Sometimes I wonder what could have been, but I have to check myself. I know now that the hustler's life is not the life for me. These days, I couldn't even sell water to an empty well. On the contrary, I would probably just give it to the well for free, knowing that water in the Northeast is far from scarce. I guess something has gone missing.

But for whatever reason, that one year was different. My mysterious greed and duplicity ran deep. In fact, it ran so deep that I once forged a signature on a card of Charles Barkley with a black Sharpie as an excuse to bump up the price. On my first grade report card, I received a C+ for "Citizenship," but surprisingly, this was not my worst grade.

My worst grade was a C- in "Handwriting." Thankfully, we now have computers. But there's no quick fix for poor citizenship, and there probably never will be.