words & images // Zac Dubasik

As published in Issue 36 of Sole Collector Magazine

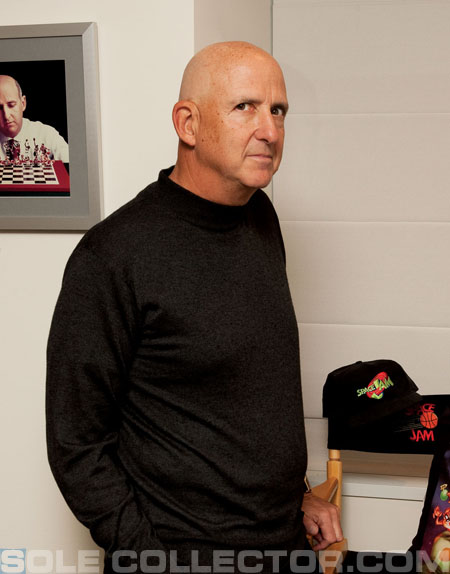

Late last year, sneaker fans around the world anxiously awaited the rerelease of the Space Jam Air Jordan XIs. While their campout conversations may not have revolved around David Falk, they very well could have. Whether they knew it or not, Falk had a lot to do with why so many people spent hours in line and on hold that day. In the broader sense, it was Falk, as MJ’s agent, who brought Michael Jordan and Nike together back in 1984, so it would be fair to say that any Air Jordan release would have been an appropriate place to speak of him. In a more specific sense, though, it’s Falk’s forward thinking that led him to market-expanding ideas like having MJ star in a movie – Space Jam, for instance, which Falk executive produced.

That type of outside-of-the-box thinking has led to some of the more interesting marketing deals in sports, especially when it comes to sneakers. The Air Jordan line, Patrick Ewing’s Ewing Athletic, Allen Iverson’s Reebok deal, Elton Brand’s Converse signature line that is sold at JC Penney, and, most recently, Evan Turner’s Li-Ning signing are all strong examples of Falk’s work. Rather than just having players he represents simply collect a check, he’s helped guide them towards much greater opportunities.

That type of outside-of-the-box thinking has led to some of the more interesting marketing deals in sports, especially when it comes to sneakers. The Air Jordan line, Patrick Ewing’s Ewing Athletic, Allen Iverson’s Reebok deal, Elton Brand’s Converse signature line that is sold at JC Penney, and, most recently, Evan Turner’s Li-Ning signing are all strong examples of Falk’s work. Rather than just having players he represents simply collect a check, he’s helped guide them towards much greater opportunities.

Falk gained a reputation as one of the most powerful individuals in sports not only through marketing deals like these. He negotiated landmark NBA deals, like multiple then-highest-in-the-League contracts, and the first $100 million deal in all of sports. What makes this track record so impressive is that he’s done it his way. No buying players at the AAU level, no being a yes-man when players wanted to hear they would be drafted higher than he knew was realistic, and no telling players to come out of school before they were ready. These days, Falk is representing far fewer players than he did at the height of his career, and that’s exactly how he wants it. At one time, he was representing upwards of 40 players at once.

Now, he has the luxury of having much more time to put towards each and every one of his clients, and even sit down for interviews like this one. I met Falk this past summer when he traveled to China for Evan Turner’s first trip to Li-Ning, where we spoke at length about hoops, marketing, shoes and even had a free throw contest – which he won. It was a great opportunity to get to know him, and a month or so later, I sat down with him in his D.C. office for this interview.

Zac Dubasik: When did you first know you wanted to be an agent?

David Falk: Originally, I wanted to be a sports lawyer. When I was in college, I always wanted to be a lawyer. I never wanted to be an astronaut, or an Indian chief, or a relief pitcher. [laughs] I can’t really say why. When I wrote my book, I traced it to a friend of mine in fifth grade. Back in the day, we used to have this ceremony at the end of fifth and sixth grade; we had something called an autograph book. It was a little book with pieces of colored paper, and everyone would write stuff in. . . . So, this one guy named Gregory Mallow, who was not a good friend of mine, told me I should be a lawyer because I was a good arguer. And I guess that pressing advice stuck. So, I always sort of expected that I’d be a lawyer. When I went to Syracuse, as a freshman on my first day of school I met the two most heavily recruited guys on the basketball team, who were on my floor. Back then, freshmen couldn’t play. We became really good friends, and I had this very, sort of innocent notion that I would represent them when they finished.

One of them actually got drafted and played in Europe. And I realized by the time I was a senior that I didn’t have a clue about what it took. I guess I was a lot like a lot of the young agents today – or some that aren’t so young. [laughs] So, I went to law school, and I worked. After my first semester – I always had a job in law school – I started just networking. My father-in-law introduced me to a gentleman in Boston who did financial planning for a lot of the Celtics, and he introduced me to Larry Fleisher, who was the head of the Union. Larry introduced me to Bob Wolf, who was a very prominent agent, who represented Larry Bird.

Back then, the business was tiny. Most of the major agents weren’t these big, mega-firms like they have today. They were individuals. Sole practitioners. They maybe had a secretary and an assistant. And none of them were hiring. And if they were hiring, they probably weren’t going to hire me. Everyone told me that since I was in law school in Washington, D.C. – I was at George Washington Law School – I should look up this gentleman named Donald Dell, who was a tennis guy. I didn’t know anything about tennis. And so I met a lot of people in Washington. I met a gentleman named Hamilton Carothers, who was Paul Tagliabue’s predecessor at Covington & Burling; he was the head lawyer for the NFL. I met the lawyer at Arnold & Porter who was the head lawyer for Major League Baseball. I just met a lot of different people. And finally I arranged to get a free internship at a small law firm that later on grew into ProServ. And that’s how I got started.

Back then, the business was tiny. Most of the major agents weren’t these big, mega-firms like they have today. They were individuals. Sole practitioners. They maybe had a secretary and an assistant. And none of them were hiring. And if they were hiring, they probably weren’t going to hire me. Everyone told me that since I was in law school in Washington, D.C. – I was at George Washington Law School – I should look up this gentleman named Donald Dell, who was a tennis guy. I didn’t know anything about tennis. And so I met a lot of people in Washington. I met a gentleman named Hamilton Carothers, who was Paul Tagliabue’s predecessor at Covington & Burling; he was the head lawyer for the NFL. I met the lawyer at Arnold & Porter who was the head lawyer for Major League Baseball. I just met a lot of different people. And finally I arranged to get a free internship at a small law firm that later on grew into ProServ. And that’s how I got started.

Who was your first actual client?

Well, what happened was, there were four partners at the firm. It was called Dell, Craighill, Fentress & Benton. The fifth lawyer was a gentleman named Michael H. Cardozo, 5th. He was sort of my day-to-day mentor. He was Donald Dell’s chief-of-staff. So, I worked for Mike, and I did a little bit of everything. I wrote contracts, I reviewed royalty reports to the athletes, to make sure their shoe deals were being paid properly. I started full-time in 1975 when I graduated law school in August. Mike left almost right after I started, to run the state of Connecticut for Jimmy Carter. It was the only state, I think, on the East Coast that Jimmy lost, and they rewarded Mike, who’s a great guy, by giving him one of the four counsels to the president. So, when he left, Mike had like 15 or 20 clients. And they just said, “OK David, these are your guys. Just take it over.” And so in ’76, the firm had signed three of the top six players in the draft. John Lucas, who went one, Wally Walker, who went five, and Adrian Dantley, who went six. I’d never met them, I didn’t negotiate anything for them, but when the contracts were done, I wrote the contracts. And then the senior guys, who didn’t want to really do what we call “babysitting” in our business, said “David, they’re yours. Take over.”

To say I was hands-on would have been the understatement of the century. [laughs] When John Lucas wanted to buy a new tire for his car, I’d call like five dealerships in Houston to see if I could save him maybe 20 bucks. Today, when a guy wants to buy his fifth Bentley, you hope you can save them more like 20 grand. [laughs] So, I was very, very hands-on. I had a lot of the older players like Kermit Washington, Roger Brown, Bud Stallworth. I probably had about 20 guys that I was day-to-day responsible for managing, and I did that probably from like ’76 until about ’80. In ’80, I sort of started getting clients on my own. After doing it for five years and learning, and watching, and working with the older guys, I finally started getting clients on my own.

So, obviously, the client you are most known for is MJ. Could you talk about how that came about?

What happened at North Carolina was our firm ProServ – Donald Dell and a gentleman named Frank Craighill, who were the two senior partners – had a very close relationship with Coach Smith. Frank Craighill had been a Morehead Scholar, which is like a scholar athlete at Carolina. And so they had represented George Karl, Dennis Wuycik and Bobby Jones in the old days. Then it really sort of clicked in about ’77. We represented a player named Tommy LaGarde, who had busted up his knee, and they got him a great deal at number nine. That was one of the deals I was actually involved with. So, from that time on, we basically got all the Carolina guys. We got Phil Ford, who was the Player of the Year in ’78, Dudley Bradley in ’79, Mike O’Koren in ’80, Al Wood in ’81 and [James] Worthy in ’82. So the players, after a while, they sort of learned what I call “the drill.” The drill was, we’d come down to Carolina, Donald and myself – he was the senior guy, I was the junior guy – and the players knew that Donald would do their first deal. They called him the ghost. They’d never hear from him again. And then I would take over and do all the grunt work, and then when the second contract came, I would do it.

By the time Michael came out of school in ’84, we went down to make a presentation. There was no recruiting allowed then. Dean didn’t allow any recruiting whatsoever. And when I say whatsoever, underline the “ever.” [laughs] He’d say, don’t call them, don’t call the parents, don’t “bump” into them, and you’ll have a one-hour presentation at the end of school. So, Dean recommended to Michael that he leave school as a junior. We went down and met him. He knew "the drill," and he signed with us. Clearly we were invited down on the strength of Donald’s relationship. I would never dispute that. Donald did his first contract with the Bulls; I had no involvement with it whatsoever. And that was the only deal that he was involved with. After that, I took over and developed a very close relationship with Michael. I felt that Michael needed to know that I was working for him. I wasn’t working for a company that represented him. I was working for him. I would try to recommend things to him and screen things for him to promote his interests.

There were a number of occasions in the first four or five years when his interests sort of collided with the firm’s interests. There was one situation where Donald had come up with an idea for Michael to play Magic one-on-one for a made-for-TV special. It was a very interesting idea, but Michael didn’t want to do it. And when I told Donald that Michael wouldn’t do it, he got very upset and asked who I was working for. I said, “I’m working for Michael. The day he doesn’t think that I’m working for him, he’s going to fire us.” Because, at that level, you need to know that someone is there 100 percent for him. Today, my former partner, Curtis Polk, took over his representation when Michael became an owner. Agents aren’t allowed to represent owners and players at the same time. And that’s what you need to know. You need to know that your advisor is 100 percent going to tell you what they think is in your best interest. After my second or third year working for Michael, he actually asked me to leave ProServ and go to work for him full-time. I really wanted to do that. For one thing, I really wasn’t being paid very much money by Donald, and it was obviously flattering for the best young player in the game to ask me to do that. But I guess I wasn’t confident enough in myself. I worried that if he got mad at me and fired me, I’d be out of the business. [laughs] So, I passed. But I think over the first four years, I earned Michael’s trust.

For the Air Jordan deal, I came up with the name “Air Jordan.” I had an extremely close relationship with Rob Strasser at Nike, who was the head of marketing, and I did all the deals. I wouldn’t let anyone in the firm do any deals, in any sport, for Nike yet. I understood what they wanted, what their MO was, and maintained that relationship. Donald had a very close relationship with adidas, and another gentleman in the firm, Lee Fentress, had a very close relationship with Converse. I was the young guy; I was looking for my own identity. I sort of found Nike when they were very small and grew with them. So, Michael came to Nike because of my relationship with Rob Strasser.

For the Air Jordan deal, I came up with the name “Air Jordan.” I had an extremely close relationship with Rob Strasser at Nike, who was the head of marketing, and I did all the deals. I wouldn’t let anyone in the firm do any deals, in any sport, for Nike yet. I understood what they wanted, what their MO was, and maintained that relationship. Donald had a very close relationship with adidas, and another gentleman in the firm, Lee Fentress, had a very close relationship with Converse. I was the young guy; I was looking for my own identity. I sort of found Nike when they were very small and grew with them. So, Michael came to Nike because of my relationship with Rob Strasser.

How much involvement did Michael have back then, as far as product and creative input?

Because Michael was a very bright guy, he listened a lot the first few years. I had a lot of involvement. Because Nike was so small and entrepreneural back then, with a lot of the early commercials, Strasser and I would literally sit down for like sushi and beer in Portland, and after a few beers, we’d get a little more creative. [laughs] I remember we did one commercial with the jet plane, and that was after our third whatever-beer-we-were-drinking in Portland. It was fun back then, because no one was doing that. No other young player had his own line. Bird didn’t have his own shoe, Magic didn’t have his own shoe, Dr. J didn’t have his own shoe – Bernard King, Isiah Thomas – none of the players had their own shoe. I think that created so much jealousy that was exhibited at his first All-Star Game, when Isiah froze him out, which he’s never admitted to, to this day. Some people at some point in their career say, “I admit I made a mistake. I did it.”

But it was unprecedented back then for an individual to have his own line. It was fun, because it gave us so much entrepreneural flavor. After maybe three or four years of learning, Michael is a very, very intelligent guy, and he got incredibly involved. He’d read fashion magazines for colors and what was coming out of Europe. And not just men’s magazines, but women’s, because he wanted to try to learn it. I think one of the reasons that Air Jordan has been so incredibly successful is that he doesn’t look at it as an endorsement; it’s his company. His name is on it, and it’s totally hands-on. He developed a very close relationship with Tinker Hatfield. Clearly, if you ask anyone, they’ll tell you it’s the best shoe. It’s the best-looking; it’s got the best tech. And it allowed the price of shoes to go up dramatically. When the first ones came out, they were like $59.99. Now . . . You could probably charge $459, and you’d probably sell just as many.

Since he was the first person with his own brand . . .

I think he was the only person to have his own brand. Not the first – the first and the last.

But do you think that someone else could have done it?

Oh yes, absolutely. I think Magic could have done it. And the reason I say that is Magic won a national championship in 1979 at Michigan State. He got drafted number one by the Lakers, which is one of the top markets in America, on a great team. He wins the NBA Title as a rookie, and Finals MVP as a rookie. So, in a 12-month period, the guy had an entire career. He had a Hall of Fame career in 12 months. He had the personality; he had the nickname. No one had to come up and say, “What should we call Earvin Johnson’s shoe?” [laughs] He was Magic, and everyone knew he was Magic. He had the smile, and Showtime back then with the Lakers. The road was paved. The problem then, and I think in many ways the problem now, is that many of the people that represent these stars don’t have the foresight, the knowledge, the talent and the creativity to know how to translate those qualities that the player has into opportunities. So, one of my frustrations is that I’m looking for the Kobes and LeBrons to raise the bar – to do something as dramatically different in the 2000s as Michael did in 1984. I think what Evan [Turner] did this year in signing with a Chinese company now that the NBA has gone global is probably the most dramatic change that there’s been since Jordan signed with Nike in 1984. And I’ve got my fingers crossed that everything will come together and work. I’ve got great respect for Brian Cupps [Li-Ning Director of Brand Initiative for Basketball]. The company is a billion-dollar company in China. The product that they’ve created for Evan has been terrific; he really likes it. And with a little luck, and the size of the Chinese market, people will look back and say that was another breakthrough deal.

You’ve been involved in a lot of unique sneaker deals, with MJ obviously, and most recently with Evan – but even with Patrick Ewing and Elton Brand. Is that something that you’ve always encouraged your guys to do?

You’ve been involved in a lot of unique sneaker deals, with MJ obviously, and most recently with Evan – but even with Patrick Ewing and Elton Brand. Is that something that you’ve always encouraged your guys to do?

I did tennis when I was very young. I was the junior agent for Arthur Ashe and Stan Smith when I came to work at ProServ. And that’s like the sun coming up in the morning, when a star tennis player or star golfer is going to have their own line of products, shoes or apparel. The person it really started with in basketball was James Worthy, in 1982. He was the number-one pick in the draft by the Lakers and he was the MVP in the college National Championship game against Georgetown when Michael sank the winning shot. Worthy got the largest shoe deal in history in 1982 from New Balance – not the largest rookie deal, the largest deal. And that sort of set the tone for Michael. My thought was that you had to try to find a company that fit the player, fit his personality and provided marketing opportunities for him. And each player is different. When Patrick Ewing came out the year after Michael, I sat down with Rob Strasser. He said, “OK, what’s it gonna be for Patrick? Air Ewing?” And I said, “No, Michael’s the Air; Patrick is the infantry. He’s a 7-foot guy in the paint – a blue collar kind of a guy. He’s not a flyer, even though he’s a great jumper. He’s the infantry.” So, we thought Patrick and Force was a better fit. Patrick ended up going with adidas, and the Force became the infantry line for Nike. That’s what I try to contribute to these individuals. I try to understand, as their brand manager, what looks good on them; what company works the best. It’s a little bit like a general manager trying to understand what players fit into a system. If you have Doug Collins as your coach in Philadelphia, and you draft an Evan Turner – Doug’s coached Michael Jordan, he’s coached Grant Hill and these unbelievably talented 6-foot-6-inch and 6-foot-7-inch swingmen – he knows how to bring out the best in Evan Turner. It’s a very special opportunity for me to have Doug Collins coach Evan Turner, because he’s been there and done it with the best. My job is to try to be like Doug Collins – having had Michael, James Worthy and Patrick Ewing – and try to understand how I can help Evan Turner connect with the best company for him. It took a leap, because we had no previous experience with Li-Ning.

How did Patrick’s Ewing line come about?

We had a very close relationship with adidas back in the day. Adidas has always been a European company; it was founded in Germany, and they have an office in France. They make great product. But I don’t think they ever really got the flavor in America with Patrick. Horst Dassler, who’s the son of the founder, died, and the company was in disarray, and they bought themselves out of [Patrick’s] contract. Then we created his own company, called Ewing Athletic. I went to a gentleman named Roberto Muller, who I always really respected, but I can’t say we had a close relationship in the day when he was at Pony. I asked him, “Can you make Patrick Ewing’s shoe all-white, no logos?” And he said, “Yeah, of course.” They were all made at the same factory, Pao Chen. He asked, “Why?” I told him, “I want him to start all over again. I need to erase the adidas past, and for the next nine months of the year, I want people to guess in Madison Square Garden what he’s wearing." . . . So we did that. And after a few months, Roberto saw the response, and people were really curious. Patrick was a big player, and it was like a new model car, when you go to the car shows and they are under the tent. So, we started the company, and it did phenomenally well. I’d have to go back and do some research, but my guess is that it sold a little bit over 100 million dollars in 1990. LeBron and Kobe probably don’t sell much more than that in 2010, and the price of shoes has probably gone up two or three times.

You mentioned that Michael is the only person to be a brand, but do you think there is still value in giving big deals to a Kobe or LeBron?

Absolutely. Tremendous value. But I think you have to understand that there’s a difference between being a brand and being an endorser. I think that if you look at someone like Tiger, for example, I’m not sure that if you study how much product Tiger sells of Tiger Woods clothes that it’s been really amazing. But if you look at what Tiger’s done for the Nike Golf brand – he took a company that wasn’t even in golf and legitimized them by himself, and the sales have been phenomenal. So, you can say Tiger has been an incredibly effective, impactful endorser for Nike, but not as incredible and impactful at selling the TW brand and the logo. And that’s not a knock; I just think Jordan is a fluke. It’s not that he’s better; I think he came along at a time when there was no one else doing it in team sports. He was a star on a worldwide stage in the Olympics in 1984, and no one expected him to do it. If you look at the chronology of stars in my world, 10 years after Michael was Grant Hill. He should have been the next guy. Properly marketed, I think he could have been the next guy. Nine years after Grant, almost a decade later, was LeBron. I’m a big LeBron fan. I think LeBron’s popularity has taken a big hit, but it’ll come back, because they are going to win, and he’s a great player. I think he has a real chip on

his shoulder to prove to people that it was a good decision, even though it might not have been well implemented. I’m just disappointed. And I’ve told this to Aaron Goodwin, who was his first agent; I’ve told this to Maverick Carter, who is his second agent, to raise the bar. You need to do in 2010 what Jordan did in ’84. To go with McDonalds, Nike and the exact same product mix 25 years later is not exactly breakthrough. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with it; it’s just not what you’d expect for a guy that coming out of high school you knew was going to be a prodigy.

Do you think it’s just a case of those companies being so well-established and writing the biggest checks?

No. I just think it’s going to require someone who’s the brand manager for the Bryant brand, and the James brand, and the Durant brand to break the mold, and do something different.

Check back this Friday on SoleCollector.com for Part 2 of our Industry Insider interview with David Falk, where he discusses the struggles of former client Antoine Walker, the world of influence that sneaker companies have on the AAU, the potential for an upcoming NBA lockout, and his most memorable disagreements with Michael Jordan.